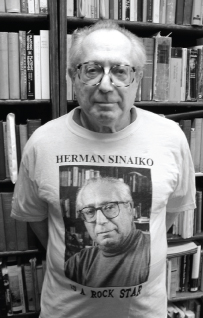

Herman Sinaiko

In Memoriam

Photo courtesy of the Core/Carrie Golus.

There aren’t many people like Herman Sinaiko around at universities: people who spend their entire lives, more than half a century, at the same institution. Sinaiko taught in the Humanities Core and in eccentric programs like Fundamentals and Big Problems and ISHUM, but he wasn’t limited to the Humanities Core or Interdisciplinary Studies in the Humanities or any of those things — he was, in some sense, the whole university. He had been so involved in Chicago’s workings for so long that, as far as I could see when I studied with him, he contained the whole thing. I once took a reading course with him on the history of American education, for which I read people like Robert Hutchins and Wayne Booth, while he simply narrated the history of the College — the original curricular debates and the late ’60s unrest and the later Core reform debates of the ’90s. There also aren’t many people who do what Sinaiko did — dedicate themselves to teaching undergraduates. He was a great supporter of student organizations, among them, this journal, for which he served as faculty advisor since its inception in 2006.

Sinaiko started his classes with Plato, and sometimes also with Homer. Greek Thought and Lit. opened with the Iliad rather than the Apology, but Sinaiko’s argument was no less Platonic. Consider the rage of Achilles, the class began. (And began, and began again. Sinaiko once explained his tendency to get so caught up in the openings of books that he rarely made it through the whole work in one quarter: “You’ll have to forgive me. I have a passion for beginnings.”) Achilles is angry that Agamemnon stole his concubine. What’s the import of such a little slight? Just look at Zeus and Hera — he insults her and they go to bed together that very night. The immortal gods don’t understand insults. They get irritated, and they cut down a few dozen men, and then they make love. But they don’t understand rage, and what it means to have your own — your family, your honor, your life — threatened. Sinaiko told a story about someone breaking into his house one night while his children were sleeping, and how, thinking of his children, he understood what it really meant to “see red”— the closest thing to Achilles’ rage he had experienced. The gods don’t understand that you can’t get these things back once they’re gone. They have all this power, but no understanding — their lives are wanton and meaningless, and in this respect, hardly better than those of beasts. We understand, and we long for things — material things and other people, but also justice and beauty and truth — precisely because we know we will die.

The wrath of Achilles costs the Greek army the lives of hundreds of men. It nearly costs them the war. The Iliad is full of dozens of deaths, each described individually. Each death matters. Our deaths matter to us; they spur us to live consciously and make living well a matter of mortal importance. These were — loosely, of course — the lectures on the Iliad. He would pound on the table and yell, “You will all die! And what kind of life will you live in light of that?” A week or two later, reading the scene in book xxiii which Sinaiko loved particularly for its dramatic recognition of this demand — the one in which Achilles comes to Priam’s tent to hand over Hector’s body — I found myself unaccountably crying over it, to the consternation of the other patrons on the second floor of the library. But to be reduced to tears by Priam’s appalling tragedy in the university library is not, after all, a final recognition of one’s mortality. It’s a hint, a moment of poetic clarity that may move one to probe further, read more, work later, sacrifice small pleasures for more substantial goods.

Valuing liberal education at Chicago meant valuing the Core, and the possibility of being told by other people who know something you don’t what is important — necessary, even — to learn. This kind of authority is rare and rarely accepted, perhaps for good reason, but perhaps not; some people might deserve such deference. Sinaiko was the first teacher I’d ever encountered who seemed to know more than the contents of a textbook. He took literature and philosophy seriously, he took his students seriously, and he remained unfazed by the demands for practical application and the accusations of irrelevance leveled at the humanities from outside the university. It may be objected that this is an education founded on prejudice, since none of us can actually know the value of a liberal education before we receive one, but all education — even one that claims to offer infinite choice but really relies on whatever ill-founded ideas have chanced into the nearly vacant mind of an 18-year-old — begins from prejudice. Starting with the Greeks is not, I think, the worst way of dealing with the difficulties of foundational prejudices.

Sinaiko’s death is a tremendous loss for Chicago, and particularly for the College, which has benefitted immeasurably from his erudition and dedication. The highest life in Aristotle’s Ethics, which Sinaiko taught in the third quarter of Greek Thought and Lit, is the contemplative life, and Sinaiko served as an exemplar of such a life for thousands of college, graduate, and even high school students. Aristotle says of such meetings that, “it would seem that payment ought to be made to those who have shared in philosophy; for the value of their service is not measurable in money, and no honor paid them could be an equivalent, but no doubt all that can be expected is that…we should make such return to them as is in our power.” Because teachers like Sinaiko are rare, their students are correspondingly numerous — Sinaiko’s reputation ensured that his HUM courses always required a pink-slip — and so, one hopes, will be the returns they make for his teaching.